"No one had any compassion or any kind of a nice word to say to us. There was no one to say, 'It's going to get better,' or, 'Don't worry.' At no time had you the luxury of hearing anything like that." —Ben Stern, Columbia Concentration Camp Survivor

"The scariest thing is not the evil, but more the people who sit by and let it happen." —Albert Einstein

For the most part, the nations of the world offered little assistance to the victims of the Holocaust. German plans for the annihilation of the Jews could not have succeeded without the active cooperation of non-Germans in occupied Europe. A long tradition of anti-Semitism aided the Nazis in their efforts. Many of the death camps were, for example, staffed by Eastern Europeans, recruited and trained by the Nazis.

League of Nations Offers Little Help

During the early stages of Nazi persecution of German Jews, few countries offered to take in the victims of persecution. This was true even after it became clear that discrimination against Jews was a deliberate policy of the German government. Although its charter forbade such actions, the League of Nations was helpless to stop Hitler's plans for the forced expulsion of the Jews. The League did set up a commission to help German Jewish refugees, but League member nations offered so little assistance that the head of the commission, James McDonald, resigned in protest. No nation offered to revise its immigration policy to meet this crisis. None offered to accept German Jews while they could still get out.

United States Keeps Immigration Quotas

The countries of the world continued to restrict immigration from Europe. The American public learned about the death camps in November, 1942, when the State Department made this information public and gave it to the mass media. It was never treated as a major news story in American newspapers.

A few Church leaders worked with American Jewish organizations to urge the government to act, but on the whole there was a deafening silence from the United States and other countries. The State Department saw no place to put the thousands of Jews that would have to come. There was no leadership from President Roosevelt to put pressure on the State Department or government officials. Despite this, several thousand Jews did manage to get out. Refugees went anywhere they could obtain a visa, China, Africa, Brazil, Japan, or India.

By late 1938, the Nazis had recognized that forced emigration of German Jews was a failure. The German Foreign Office noted that the world had closed its borders to the Jews. How could the Jews leave Hitler's Germany if there was now no place for them to go?

Immigration Quotas Not Filled

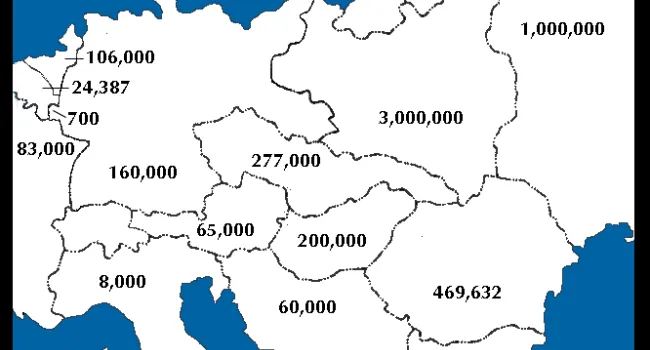

Throughout early 1939, the United States admitted about 100,000 Jews from Germany and other Eastern European nations. However, this figure represented only about one-fourth of the places available in the United States for refugees from Nazi Germany and occupied Europe. Nearly 400,000 openings were not filled. Certain officials within the State Department resisted attempts to fill the quotas allowed for Jewish emigration. Reasons for this are complex. Throughout the Depression years, some Americans feared job competition from incoming refugees. Anti-Semitism also played a part in American policy toward the refugees. Great Britain, Canada, and a number of Latin American countries had policies similar to those of the United States.

St. Louis Refused Entry

While the doors to official emigration were closing, many still tried to leave their country for a safe haven abroad. Counting on the goodwill of the United States and Canada, several shiploads of German Jews sailed for North America in 1938 and 1939. In May, 1939, 937 German Jews boarded the "St. Louis," bound from Hamburg, Germany, to the United States. The passengers on the "St. Louis" already had American quota permits but did not yet have visas.

The "St. Louis" reached Cuba. For over one month, the passengers waited for their papers to be processed by American authorities. When permission was eventually denied by the United States and a number of other nations, the "St. Louis" was forced to return to Germany, where most of the passengers died in concentration camps.

The world's religious communities did little to protest the mistreatment of Germany's Jews. Before the war, few Catholic and Protestant clergymen in Germany officially condemned Nazi treatment of German Jews. Church leaders in Germany looked aside when in 1935 the Nazis implemented the Nuremberg Laws.

Monasteries and Convents Offer Refuge

After war broke out, however, a number of Catholic and Protestant leaders did offer some assistance to Jews, including false baptismal certificates and refuge in monasteries and convents. In Germany, Pastor Martin Niemoeller, a World War I hero, eventually spoke out against Nazi policies, as did a few other high-ranking German religious leaders. But such protest was limited and came too late to make a difference.

The Vatican, under Pope Pius XII, was silent throughout the war. Even when Italian Jews were deported from Italy within view of the Vatican, the Pope offered no official condemnation of German policies.

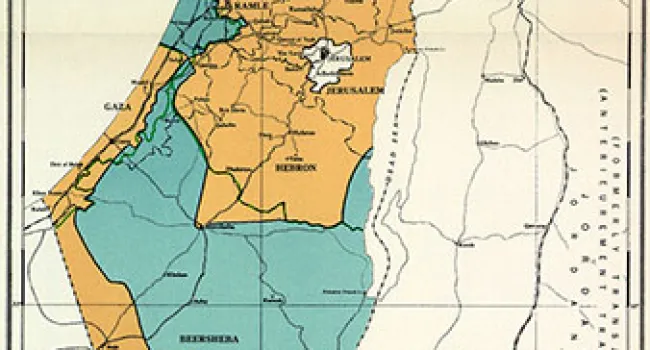

Denmark and King Christian

Many courageous individuals and nations did attempt to stop the Holocaust. The Danish government refused to accept German racial policies, even after that nation was occupied in 1940. The Danish king, Christian X, forcefully told German officials that he would not permit the resettlement of Denmark's small Jewish population. In 1943, when the Nazis ordered the deportation of the Danish Jews, word was quickly sent throughout the country to help the Jews escape to Sweden. The rescue that followed saved nearly 7,000 lives. This number represented over 90 percent of Denmark's Jewish population.

Italy and Bulgaria

Although Italy and Bulgaria were allied with Germany in the war, both nations resisted German orders to deport Jewish citizens. The Bulgarian king and government slowed efforts to deport Bulgarian Jews, as did the Italian government. Despite severe German pressure and local anti-Semitic political parties, both governments saved three-fourths of their Jewish citizens from deportation and death.

Raoul Wallenberg

While the Hungarian government at first resisted efforts to deport Hungarian Jews, it finally agreed to let the resettlement begin in 1944. Raoul Wallenberg (pictured above), a Swedish diplomat working in Budapest, gave tens of thousands of Swedish passports to condemned Hungarian Jews, often handing out these documents to people already loaded on German trains bound for the death camps.

Wallenberg's efforts during 1944 saved about 20,000 lives, and he sought shelter for hundreds of others in safe houses protected by the Swedish government in Budapest. Suspected of spying for the Allies, Wallenberg was arrested by the Soviets after the liberation of Budapest in 1945 and was never heard from again.

There were also many Polish citizens who aided Jews during the war. A few Polish resistance groups supplied arms to Jewish fighters in the various Polish ghettos. Zegota, an underground organization of Polish Catholics, hid Jews from deportation. There were many instances of individual Polish citizens hiding Jews in their homes and farms until the end of the war. However, most Polish Resistance groups ignored, or even persecuted, Jews who escaped from ghettos and camps.

Holocaust Museum Honors Rescuers

At Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Israel, those non-Jews who aided Jews during the war are honored as Righteous Gentiles. Hundreds of trees have been planted along a pathway to remind museum visitors of the courage of non-Jews who, despite risk to their own lives and families, refused to stand by while others were being persecuted or murdered.