by Jimmy Gilmore. Gilmore is a Film and Media Studies major in the South Carolina Honors College at USC. This paper was written for the Spring 2008 class "Folklore and Film."

“Well, Charlie, I guess I write about people like you…the common man,” says Barton Fink to insurance salesman Charlie Meadows in the Coen brothers’ 1991 comedy Barton Fink. Barton, an intellectual who hides out in a stuffy hotel room while trying to write an important film about common people, seems almost emblematic of writer, director, producer team Joel and Ethan Coen. As filmmakers, they have built a distinct career off the film noir, screwball comedy, crime, and thriller genres of classic Hollywood. Despite their diversity, all their films have been informed by a singular underlying thread: their treatment and exploration of the common man and small American culture. Often setting their films in specific times in the past and in distinct regions of America, the Coens embed their screenplays with a distinct brand of language designed to reflect the culture of each film’s setting.

Though their astute observations provide much of the subtle humor of their films, the brothers have systematically constructed a history of twentieth century America ruled by mindless commoners; instead of treating their subjects with respect and veneration, the characters of their films are satirized, exaggerated, and lacking sense. Ultimately, as their career progresses, the Coens seek to define the common man, to explicitly find who he is and what constitutes his ideology. However, this leads to a drastic denial of culture and a belief that it is better to escape the trappings of ethnicity than be succumbed to identification within a singular group.

As mentioned before, Joel and Ethan share more than a little in common with the titular protagonist of their 1991 film, and that character and film serve as a sufficient jumping point to examine the cultural ideas behind each of their films. Like the brothers, Barton Fink is Jewish, and he comes out of a very intellectual New England circle – Ethan studied philosophy at Princeton, while Joel studied film at New York University. Barton reaches critical acclaim with his play about working-class fishmongers, a culture he seemingly knows nothing about but manages to infiltrate and analyze in an artistic manner. This situation grows similarly out of the Coens’ first film, Blood Simple (1984), which deconstructs the film noir genre while incorporating the culture and language of common, working-class Texans and their human failings. Their subsequent film, Raising Arizona (1987), similarly set among the trailer park-dwelling, often-criminal working class of the Southwest, prominently displays individuals outside the realms of common sense and proper English syntax, exaggerating their language and mannerisms to lampoon the seemingly dumb culture. Only when they attempt to write about something else, the Irish mafia in the midst of Prohibition for their film Miller’s Crossing (1990), do the Coens become stuck. In reality, they suffered immense writers’ block while writing their crime drama, and from that struggle emerged Barton Fink, a film as self-referential as it is unflattering in its portrayal of screenwriting ineptitude.

Barton, assigned to write a simple B-movie wrestling picture for a Hollywood movie studio, feels the need to make something important. He gets one paragraph into his film, which sounds suspiciously like his previous artistic triumph, before becoming distracted by his neighbor, Charlie Meadows. Barton meets him while dressed in a full suit, a tie, and glasses, while Charlie’s overalls, undone shirt, and lack of tie complements his distinct physical difference from Barton. The artist refuses to shake his neighbor’s hand, apparently disgusted by this rude interruption; Barton rejects association with the very people he props up in his work. As the two converse, Barton attempts to make his work sound important; he is trying to “forge something real out of everyday experience…a theater for the masses.” Charlie, exuberant about the notion, tries to tell Barton some stories about his “everyday experiences,” but Barton promptly cuts him off, spouting more of his empty ideology and eventually condescending Charlie until he leaves Barton in peace.

Charlie constantly seems more in tune with basic human emotions than Barton, providing an interesting foil for the protagonist. Charlie’s life is of the real world; his job revolves around making connections with people. To him, “they’re more than customers;” he seeks an actual emotional connection and feels his job satisfies “a basic human need.” Barton, conversely, occupies the self-proclaimed “life of the mind,” and in his scenes with Charlie he constantly turns away from him or makes disgusted faces at him. The people he writes about are less than people: they are tools he uses for his grand artistic work. Life is not about emotional connection for Barton; it is about establishing himself as a great creator, but his “life of the mind” seems to be a life rooted securely in his own mind.

In a later scene, Charlie helps teach Barton about wrestling for his picture, and he promptly pins him to the ground. Seconds later he pleasantly chuckles, “I wouldn’t be much a match for you at mental gymnastics,” again highlighting the distinct relationship between the real and intellectual the two embody. Despite Charlie’s pervasive offers, Barton refuses to look to him for help in constructing his portrait of the common man. In one scene, Barton tries to slide his shoes on while writing, only to discover he accidentally received Charlie’s from the hotel’s shoe shining service. The shoes are much too big, and in a metaphorical parallel, Barton is unable to fill Charlie’s shoes; he cannot figure out how to step into the shoes of the common man and adequately portray his vision on the page. Ironic, since Barton refuses to stop talking about his artistic schemes when Charlie visits him, while Charlie can never quite summon the elevated vocabulary to keep up with Barton – this in turn comments on how important language is within the Coens’ cinema and how each social group seems to have its own distinct way of communicating; Barton at one point even tries to “put things in [Charlie’s language” so he can understand what he is trying to say.

Only when Charlie is revealed to be serial killer Karl Mundt does Barton finds inspiration to finish his screenplay. The stereotyped common man becomes a deranged German, and in this hidden dark side of the simple common man Barton has found his inspiration. He phones his agent to tell him, upon completion, it is “the most important thing I’ve ever written.” Not by coincidence though, the final line of his screenplay matches the final line of the play that made him famous: Barton Fink has merely regurgitated his one great idea in a vain attempt to continue his supposed legacy of dissecting the common man. Even as he celebrates among a party of young women and Navy soldiers, Barton denies the young soldier a dance with a girl, for he is “celebrating the completion of something good!” Barton rejects the common man by again propping himself on a level of artistic supremacy.

Charlie returns at the film’s climax to set afire the hotel that has long served as he and Barton’s imprisonment. He sets Barton free from the room, informing him he fails because he does not listen. Barton believes he is an artist, but encloses himself within the walls of his hotel room, never letting himself interact with and try to understand that which is right in front of him. He never listens to Charlie’s stories or advice, merely lamenting about how difficult his profession is. As Charlie says, “You think you know pain? You think I made your life hell? Take a look around this dump. You’re just a tourist with a typewriter, and I live here Barton, don’t you know that? And you come into my home, and you complain that I’m making too much noise?"

Therein lies the fundamental idea behind the Coens’ work. They take on the mold of the intellectual artist concerned with a cinema of the common man, for their films all revolve around simple people caught up in fiendish plots. In their search for the common man, they traverse cultural groups and small pockets of American life, but as they do they exaggerate the language while belittling the intelligence. The Coens do not understand that their films reflect peoples’ homes; that they themselves are tourists with typewriters, feeling free to comment on working class society however they see fit. Much as Barton sees no intelligence in Charlie and yet still tries to create a “theater for the common man,” so too do the Coens aim to infiltrate the cultures of their films.

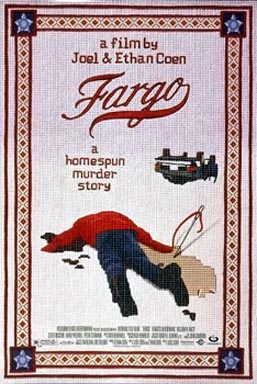

If Barton Fink defines the principle concern of the Coens’ cinema, then Fargo (1996) would be among their most harmless satires, politely poking fun at the North Dakota culture while ultimately asserting the supremacy of normality at film’s end. The characters inhabiting the film seem almost as dense and monochromatic as the bleak white snow that winds its way through the compositions. The native characters speak in a very particular diction, established through the constant repetition of several phrases and a distinct speaking pattern. Language, as in many Coen films, becomes the key element of establishing culture. The strong use of regional dialect makes many of the characters seem stupid or ignorant. Granted, this stupidity is reinforced through behavior: Jerry constantly stumbles over his own words and cannot make sense of any given situation, his wife acts like an object who can only sit in her place, while the other minor characters all act as if they have little idea what they are doing, just wandering through this world, oblivious to the action around them.

The film’s two villains – Carl Showalter and Gaear Grimsrud – encompass and comment on this use of language to define the characters. Carl talks constantly, inserting his cocky and often foul-mouthed opinion as often as possible. Even when he tells Gaear he will stop talking, he continues to plow along, aimlessly repeating himself. Carl fits nowhere into the culture; his voice and behavior contradict and intrude upon the North Dakota culture. He kidnaps the innocent Mrs. Lundegaard, becomes an accessory to several murders, and ultimately shoots Wade Gustafson and a ticket taker in cold blood. Carl is dangerous because he evades being pigeonholed by a definable culture.

His partner, Gaear, is dangerous because he rarely uses language. He comes from a foreign culture, evident through his poor grammar and thick accent, but he barely talks. His lack of communication goes against the flow of every other character in the movie, all of who talk chronically. Gaear is much more violent than Carl; almost all the individuals he murders are members of the simple North Dakota culture, and his late-night blood bath serves as catalyst to the film’s second act and introduces protagonist Marge Gunderson. The firm basis of the culture in Fargo derives itself from the notion language as accent and constant transmission, a culture founded on the need for constant communication to create a community identity.

Amidst this conflict between the decidedly simple native culture and the outsiders who bring violence into it comes cop Marge Gunderson. She refutes the film’s position on culture. She projects more foresight than any other character in the film, carefully piecing together the crime scene on the side of the road. She corrects Lou’s police work, while moments later embodying the simple commoner by sitting down for a quick Arby’s lunch with her husband. Marge is most certainly a part of this culture, her mannerisms and dialect dictate her as such, but she simultaneously seems to escape it, to become better than the others in the film. She is the only female character given a semblance of intelligence. Fargo comes from a world of normalcy, and Marge is almost as common as it gets in this society. She eventually captures Gaear and helps restore justice by using her intuition and courage, exercising her job when she must.

Fargo allows the satirized culture to come out on top. It is most certainly a “theater for the common man,” extrapolating extraordinary circumstances into the most natural and plain of worlds. The film’s main male characters – Jerry, Carl, Gaear, Wade – all depend on a connection to their money. They all die or become incarcerated because of their adoration of it, their dream of having more than what they have. It takes Marge’s common sense to remind them, “there’s more to life than a little money, y’know.” Marge comes out on top, supplanting those who maneuver outside of her culture’s principles. As she says at film’s end, “I’d say we’re doing pretty good.” She gleans the value of her own life by seeing the poor judgment and actions of others.

Fargo allows the satirized culture to come out on top. It is most certainly a “theater for the common man,” extrapolating extraordinary circumstances into the most natural and plain of worlds. The film’s main male characters – Jerry, Carl, Gaear, Wade – all depend on a connection to their money. They all die or become incarcerated because of their adoration of it, their dream of having more than what they have. It takes Marge’s common sense to remind them, “there’s more to life than a little money, y’know.” Marge comes out on top, supplanting those who maneuver outside of her culture’s principles. As she says at film’s end, “I’d say we’re doing pretty good.” She gleans the value of her own life by seeing the poor judgment and actions of others.

Fargo makes a plea for culture. The violence in the film comes exclusively from the outside characters infiltrating inward, and it takes a member of that culture to thoughtfully restore the social order. In the context of the original thesis, the film definitely satirizes the culture, but brings the satire back around to show the need for ethnicity, and for community identification. There is nothing in the movie to suggest, however, that the common man has succeeded in a dramatic way, only staved off the intruders. Only Marge, by balancing her work and her family, by supporting her husband and having her child, can calmly sleep through “two more months.” She does not undergo a change, but slips back into the monotone landscape of her culture and its values after solving the problems.

Additionally, the conflict in Fargo emerges from greed and money. The Coens often focus their films around a struggle to attain money, as if possession of it can allow for an escape from prescribed social class. Jerry seeks money through a kidnapping scheme, the landscape of O Brother, Where Art Thou? lacks money, Ed Crane tries to set up an elaborate blackmail scheme to get rich and quit his job in The Man Who Wasn’t There, while Llewelyn Moss steals two million dollars to try and forge a better life in No Country for Old Men. As the Coens investigate the trappings of small culture in the remainder of their films, it becomes those ties to money and other material possessions become the downfall of man. To succeed, it becomes necessary to be freed of all attachments, physical and cultural.

In the light of finding a heroine capable of representing the common female, a part of and yet apart from her surroundings, Joel and Ethan Coen would send the direction of their next three films towards defining the common man. In true Barton Fink form, the protagonists and surrounding secondary characters of The Big Lebowski (1998), O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), and The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) portray the plight of the common man, but in looking for a concurrent definition, they only strip away the possibility of man. While Fargo focuses on the culture as a whole and the return to normalcy after a violent assault on the people, these three films focus more on the individual common man and what he stands for. These men try to cling to community identity, and through it they either succeed or fail.

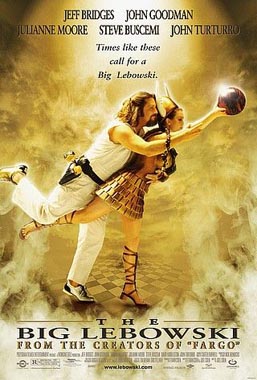

The Big Lebowski examines the role of community identity in the formation of culture. The protagonist and his so-called friends revolve their lives around the next bowling game. The opening credits montage through the bowling alley uses varying camera speeds and lighting to help paint bowling as a kind of haven, an escape from the opening scene’s bizarre scenario of “The Dude” having his rug peed on. Throughout the film, the bowling alley serves as a kind of meeting place, an intermission between important plot developments that allows the Dude and his teammates Walter and – to a lesser extent – Donny to discuss the evolving plot. Walter’s continuing mantra, “fuck it Dude, let’s go bowling,” is always uttered in moments of despair, as if bowling is a therapy to him. For Walter, a man still scarred by the events of Vietnam, a world “without rules,” bowling offers a sport that allows him to exert his destructive energy while simultaneously fitting into a system of rules. Deviation from those rules, as when fellow bowler Smokey accidentally “steps over the line,” incites Walter into outrage; he needs structure in his life. These seemingly random individuals all cling to the common identity of the bowling alley for the structured escape it provides from the chaos of the exterior world.

The Big Lebowski examines the role of community identity in the formation of culture. The protagonist and his so-called friends revolve their lives around the next bowling game. The opening credits montage through the bowling alley uses varying camera speeds and lighting to help paint bowling as a kind of haven, an escape from the opening scene’s bizarre scenario of “The Dude” having his rug peed on. Throughout the film, the bowling alley serves as a kind of meeting place, an intermission between important plot developments that allows the Dude and his teammates Walter and – to a lesser extent – Donny to discuss the evolving plot. Walter’s continuing mantra, “fuck it Dude, let’s go bowling,” is always uttered in moments of despair, as if bowling is a therapy to him. For Walter, a man still scarred by the events of Vietnam, a world “without rules,” bowling offers a sport that allows him to exert his destructive energy while simultaneously fitting into a system of rules. Deviation from those rules, as when fellow bowler Smokey accidentally “steps over the line,” incites Walter into outrage; he needs structure in his life. These seemingly random individuals all cling to the common identity of the bowling alley for the structured escape it provides from the chaos of the exterior world.

The film also seeks to comment on class relations, exhibited most predominantly by the presence of two characters named Jeffrey Lebowski – the “Dude Lebowski” and the “big Lebowski” – occupying two ends of the economic spectrum. Throughout the film, the Dude finds himself confused in the presence of these social elites; the Big Lebowski talks down to him and yells at him to “get a job!” On the surface, it seems the Dude is nothing more than a bumbling moron – he writes a check for milk, carries no ID except a grocery store discount card, and steals phrases he hears from others to use in his conversations throughout the film. However, the Dude manages to expose the Big Lebowski as a phony while retaining his honor and his haven – “The Dude abides,” as he triumphantly declares. The common man again succeeds within the world of the plot, but as in Fargo, the Dude ends the film returning to a game of bowling, locked in his culture without experiencing significant change.

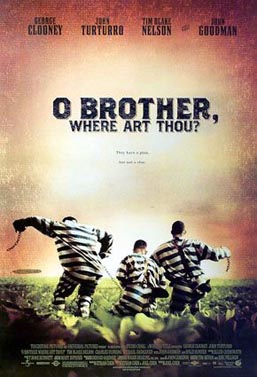

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) turns concern to the South during the Great Depression. Like Fargo and The Big Lebowski before it, the film deals strongly with money, or the lack thereof. Setting the film during the heart of the Depression, when the common man has been stripped of everything but his dignity, allows the Coen brothers to explore yet again the desire for money and the trappings of social standing. The film’s three protagonists, led by Everett McGill, have escaped from prison to search for a treasure. Following their journey across the state of Mississippi allows the film to not only to explore pockets of society, but also provide a meditation on the power of fellowship and unity.

The society of O Brother seems disrupted by the lack of money. Rules that would typically order the society and construct a system of moral ethics have given way to a world where, as Everett remarks, “everybody’s looking for answers.” For example, Pete’s cousin tries to turn him in for the reward money even though they are kin because “times are hard.” Tommy supposedly sells his soul to the devil in order to learn to play the guitar and make money. Also, Big Dan Teague becomes attracted to Everett and Delmar over the mere sound of a dollar bill. In this world, absurdity seems to know no bounds when money is involved: George Nelson, who gladly robs banks to bolster his own personal fortune during these tough times, even goes as far as to shoot cows on sight while being pursued by the cops.

Emerged in the chaotic world around them, the protagonists – especially Everett – seem completely clueless and ignorant. Everett believes he is “endowed with the gift of gab” and the only one of the three with the “capacity for abstract thought.” He constantly runs his mouth, trying to create grand philosophical statements and rationalize all situations, but as with most of the Coen brothers’ protagonists, only finds himself running senseless repetition. When cornered by the law, the only statement he can sputter is “damn, we’re in a tight spot,” repeated over and over. Delmar is also foolish enough to believe Pete becomes turned into a toad after their encounter with the sirens.

“Bible salesman” Big Dan Teague easily dupes Everett, beating him and taking all his money. Because Big Dan is also “endowed” with the gift of gab, Everett sees him as his friend; he cannot possibly understand why a man of similar standing would take advantage of him. Everett is filled with delusions of grandeur, but as an individual he constantly fails at realizing what happens around him; he calls himself an “astute observer of the human scene” mere seconds before Teague attacks him with a tree branch. Teague encapsulates a sector of the society, for he is a con man willing to do anything for the money. While Everett sees many of the characters in the film as people to be taken advantage of, such as the blind radio DJ, Big Dan manages to get the better of him, catching him off guard through his eloquence. If language is, as it has been throughout the Coens’ films, a parameter of cultural identification, then Big Dan manages to infiltrate the culture to take advantage of it, echoing the Coens’ position as filmmakers. He swoops in to physically attack Everett and Delmar, just as Gaear and Carl did in Fargo, and to rob them of their money for his own greedy gain. He even screams “it’s all about the money, boys,” as he vicious beats Delmar.

In O Brother, Where Art Thou? the culture has obviously become divided. The values and identity seem split apart, perhaps signified even more by the heated gubernatorial election currently in progress. The film suggests that music creates identity. After the boys sing “Man of Constant Sorrow” as The Soggy Bottom Boys, initially done to take advantage of the blind radio DJ’s money, the song becomes a hit and begins to tie the split community back together. Music in the film has an almost seductive power; the sirens take advantage of the trio by singing them a lullaby. This power manifests itself most potently in “Man of Constant Sorrow,” and at the climax of the film the song is performed as Pappy O’Daniel takes control of the election and pardons Everett and his companions for their crimes. Later, the lawman hunting the boys does not believe that they are pardoned because he “doesn’t have a radio” – he could not hear the music unite the divide.

In O Brother, Where Art Thou? the culture has obviously become divided. The values and identity seem split apart, perhaps signified even more by the heated gubernatorial election currently in progress. The film suggests that music creates identity. After the boys sing “Man of Constant Sorrow” as The Soggy Bottom Boys, initially done to take advantage of the blind radio DJ’s money, the song becomes a hit and begins to tie the split community back together. Music in the film has an almost seductive power; the sirens take advantage of the trio by singing them a lullaby. This power manifests itself most potently in “Man of Constant Sorrow,” and at the climax of the film the song is performed as Pappy O’Daniel takes control of the election and pardons Everett and his companions for their crimes. Later, the lawman hunting the boys does not believe that they are pardoned because he “doesn’t have a radio” – he could not hear the music unite the divide.

The redemptive and universal power of music also reveals a kind of cultural identity: all the music featured in O Brother derives from blue grass music of the time period. “Man of Constant Sorrow,” in this sense, creates a community identity absent from throughout the film. Everett, who seems out of touch with the culture around him, ironically becomes one of the forces capable of uniting this disparate culture. In O Brother, as in The Big Lebowski, the common man again comes out as victor by maintaining a system of principles that slowly translates across an absurd and out of touch community.

If in The Big Lebowski the bums do end up winning, exposing the empty snobbery of the upper class while retaining a sense of community identity, The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) refutes this notion almost entirely, exposing the protagonist – and, by proxy, the common man – as weak and incompetent, doomed to fail. Ed Crane, the man of the title, works at a barbershop, even though he does not consider himself a barber; he “married into it.” Unlike The Dude or Everett, who crowded their respective films with language and personality, Ed seems quiet and removed from his world. If the common man of The Big Lebowski sought to maintain a community identity, the common man here insists on removing himself. Ed does not like to talk, nor does he like to entertain. He “just cuts the hair.” In this way, Ed tries to mold himself into his class. The other common man of the film, Ed’s brother-in-law and one of the owners of the barbershop, Frank Raffo, seems almost the opposite. Frank talks about everything, but as Ed points out, “if you’re eleven or twelve, Frank’s got an interesting point of view.” Much as Everett flaunts his vocabulary without being constructive, Frank sees a need to fill all gaps with words. He comes from a common family; at a wedding he gets drunk, rides on the back of a pig, and wins the blueberry pie eating contest. Frank seems to represent the Coens’ former notion of the common man established in their earlier films: a simple person designed to fit into his place, teetering on the edge of stupidity.

Though Ed is associated with this culture via his marriage, he seems disgusted by his world. He hates his job, and knows his wife is cheating on him with her boss. Ed seems desperate to escape his social status, playing right into the hands of a con man and losing ten thousand dollars. Like The Big Lebowski before it, The Man Who Wasn’t There also participates in an underlying commentary on social hierarchy. When Ed’s wife, Doris, is accused of murder, Ed’s lawyer flatly tells him, “I’m an attorney, you’re a barber. You don’t know anything.” As Ed later says, via voiceover, “I was a ghost. No one saw me and I didn’t see them. I was the barber.” Ed’s position in this world, behind the heads of those whose hair he cuts, makes him invisible.

Whereas the protagonists of the Coens’ earlier films triumph because of their hidden versatility or their principles, Ed has none. When he goes on trial for a murder he did not commit, Ed talks about how his lawyer tried to present him to the jury:

He told them to look at me, look at me close. The closer they looked, the less sense it would make. I wasn’t the kind of guy to kill a guy. I was just the barber, for Christ’s sake. I was just like them: an ordinary man living in a world that had no place for me, yeah…but not guilty of murder. He said I was modern man, and if they voted to convict me, well, they’d be putting the noose around themselves. He told them not to look at the facts, but at the meaning of the facts. And then he said the facts had no meaning.

Ed ultimately fails, and is sentenced to die at the electric chair. His last words beg for language, for the ability to tell his wife “all those things they don’t have words for here.” Though unable to conjure eloquence in his life, Ed pleads for it in death, as if to die would be to possibly succeed at finding his voice. Though the film’s title applies to not only one but two murders during the course of the film, it also applies to Ed’s position as the common man. He is, compared to the protagonists of other films, not there, an obedient servant who “just cuts the hair” until he dies, unable to find an identity or maintain a moral principle throughout the film.

The death of the barber, the common man, would eventually erupt into the death of culture in the Coens’ No Country for Old Men (2007). Returning to rural West Texas, the terrain first infiltrated in Blood Simple, the film posits that the law has no control, as it did in Fargo, that culture groups are destroyed because of their inability to overcome the identity that has turned from saving grace into handicap, and ultimately it is a lack of culture and an adherence to principle that leads to survival. Since the common man had been reduced to nothing from The Big Lebowski to The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men sets its sights on demolishing the values and principles of small culture, echoing and revoking the themes of Fargo.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell seems to suffer from clinging desperately to a community identity that no longer exists. His opening monologue expresses his yearning to mimic the old lawmen of his father’s era who lived in a world where it was not necessary to draw a firearm to maintain the peace. Ed Tom does not understand the increasingly violent world, saying quite bluntly, “I don’t want to go out there and meet something I don’t understand.” This fear inevitably permeates his character throughout the duration of the film. While he shows great skill at establishing the events of the crime scenes, Bell spends much of the film sitting in diners, spilling over the paper and commenting on the unnecessary increase of violence in the contemporary world instead of trying to catch up to Llewelyn and save him. He refuses to go back out to the various crime scenes, saying he has nothing else to learn from them. As Bell also observes in his opening monologue, “a fellow would have to say, alright, I’ll be part of this world.” He seems almost unwilling to stand up and be a part of this world he sees as increasingly chaotic; despite all his talk about its terrors, he does nothing to fix it. Bell says he wants to dedicate himself “daily anew,” yet he never does. Bell is a character of language, not of action. His methods, or lack thereof, contrast with Marge Gunderson, who used her skill to uncover the criminals in Fargo despite her pregnancy handicapping her.

Bell’s refusal to participate in the society ultimately defeats him. He has his deputy Wendell do most of the fieldwork for him, not drawing his gun until the climax of the film, when he arrives too late to save Llewelyn. Bell wants to restore justice to this corrupted world, but all he manages to do is lament about the society he is trying to protect. In his conversation with the El Paso Sheriff, the two sit in an insular booth, commenting on how kids these days show no respect, and it is “all about the money and the drugs.” The two seem stuck in a vacuum without a community identity. This lack of clear identity sets them apart from the characters of Fargo; whereas the community of that film was strengthened by its common identity, the scattered and disjointed working class of No Country for Old Men is incapable of survival.

It is this reluctance and this feeling of being “overmatched” that prompt Bell to retire. He visits his ex-sheriff uncle Ellis, now confined to a wheelchair in a small house in the middle of nowhere, cut off from society. He searches for validation from his uncle, but receives none. As Bell did earlier to convince Carla Jean to see his point of view, Ellis tells him a simple story about his great uncle. Bell does not receive the validation he so desperately looks for, instead only receiving the solemn heed that “you can’t stop what’s coming.” He ultimately ends as the film as he began it, reflecting on his father. He now sees the world as a barren landscape, a place he does not wish to occupy, but in his father – in that bygone era – he still sees hope, and he wishes to be a part of that world. This identity crisis takes the shape of a culture crisis in Bell’s character. His age leads him to disassociate himself from his community, but as the film further tries to say, the community itself has begun to rot from the inside out.

Antagonist Anton Chigurh infiltrates and attacks that small community. Chigurh is the only character in the film not associated with either a culture or social group, making him a kind of God-like presence. He walks around the film “like a ghost,” constantly eluding the common citizens and killing them with ease; his bizarre haircut and pale complexion make him stand out against the rest of the characters, but they never seem to notice him. His weapon of choice, a cattle gun, reflects his worldview that men are cattle. He sees himself as set free, uninhibited by the trappings of the mundane working class. The gas station attendant disgusts Chigurh for marrying into a job, for being stuck in an unrewarding cultural system. What sets him apart from Bell or Moss, aside from his distinct lack of culture, is his adherence to a strict set of principles. Unlike Bell, who tosses about promises to himself without fulfilling them, Chigurh makes good on everything he says he will do; he even goes back to Carla Jean’s house to kill her, just because he gave his word he would.

Chigurh systematically strips away the culture around him, killing those he comes across without hesitance. Chigurh’s actions, and the actions of those he opposes, reveal a distinct deterioration of those slightly exaggerated in Fargo. People like the old gas station attendant try to communicate with Chigurh, but he sees nothing worth talking about. Instead, the old man becomes easily confused, never once telling Chigurh how much his gas costs. His social status enrages Anton. Additionally, Llewelyn Moss echoes many Coen Brothers protagonists by wanting to escape his status in his culture. Moss’s fault is his failure to listen: he thinks he can take on Chigurh, he puts Carla Jean in peril, and despite his resourcefulness and cunning he fails to seek Ed Tom’s help and see “what’s coming.” Moss’s death, then, destroys the common man as it did in The Man Who Wasn’t There, but it punishes him for trying to be more than he is. However, if Moss is punished for trying to be more than what he is, and Chigurh kills citizens for being stuck in a single spot for their lives, then what is left for culture?

It seems Joel and Ethan deny culture the potential to thrive. It is dead and hopeless; by clinging to it the common man will only find his own death. If the common man is to die, then the death of an entire culture for its feeble decisions and meek lifestyle is not far behind. The Coens position themselves from the angle of Barton Fink, looking at cultures and at common men through a typewriter. They are not ethnographers, but they attempt to infiltrate cultures through a satirized and exaggerated display of linguistic patterns. At the end of No Country for Old Men, Anton Chigurh escapes with the two million dollars, leaving all the other characters dead or ruined. He succeeds because of his adherence to principle. Ed Tom Bell does not follow through on anything he says. Marge Gunderson sticks to her moral code, solving the crime while remaining a simple, upstanding citizen. The law prevails through maintaining a concurrent thread with the morals and the culture – Marge fits in with her surroundings. Ed Tom, on the other hand, is unable to find his place in the culture, and he does not establish a set of morals that parallel his actions. Anton, as evil as he may be, manages to establish a set of laws to guide his actions. He may not mesh with the culture, but it becomes the principles that are the guiding force.

Barton Fink fails because he too does not follow through with his ideas. He strives to create a theater for the common man, but his personality makes him disgusted by and fearful of those he tries to reach in his work. Ed Crane has no principles and no real culture. He is the barber, the common man, but his inability to find himself and a place for himself ultimately defeats him. Even the bums of The Big Lebowski remain true to their beliefs; Walter refuses to live in a world without rules and The Dude uses his own limited resources to retain his identity. The culture in Fargo seems the warmest, for the members of that community aid the law and each other to remove the cultural outsiders and restore order. The opposite is true for No Country for Old Men – the culture lacks definite principles, and when this is combined with a lack of identity, the culture fails. Only through the development of principles can an individual hope to succeed.

Life is not based on a cultural identity, but rather an individual identity; there can be no communal success without the individuals. If the Coen brothers try to be Barton Fink, to write about the common world and create a theater for the common man, they fail as much as he does. They do not celebrate the common man, but rather defeat him. Nor do they portray culture realistically; they satirize, distort, and ultimately mock it. As their films evolve, it becomes clear that culture is dead to them. Marge Gunderson succeeds at catching Gaear Grimsrud and Jerry Lundegaard because she is tied to her moral principles. She does not deviate from them, and although her culture informs those principles, her culture is not what makes her a strong cop. Likewise and conversely, it is Ed Tom Bell’s refusal to invest in a strong set of convictions that leads to his downfall. Because Chigurh adheres to strict principles, and perhaps because he refuses cultural identification, he exceeds as an emblem of what the common man should strive to be.

Though at one time capable of uniting cultural divides and succeeding in the continuation of culture, as in The Big Lebowski and O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the Coens seem to experience a change of heart by the time they create The Man Who Wasn’t There. From that point on, the common man seems incapable of stopping what is coming, forced to confront his own mortality and his failing against higher powers. Death, as seen in Ed Crane’s termination and Ed Tom Bell’s dreams of uniting with his father, is not a lamentation but an escape, a chance to transcend the turmoil of earth and, in the spirit of language, understand “all those things they don’t have words for here.” The cinema of the common man does not celebrate the common man at all. It forces him to confront his failings and accept that although community identity can succeed in the short run, as can material possessions, it ultimately serves as a handicap that will lead to death. In the grand scheme of things, it becomes necessary to renounce culture, to separate from it, and escape from this country – no country for common men.